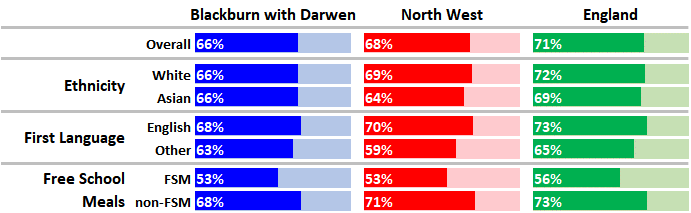

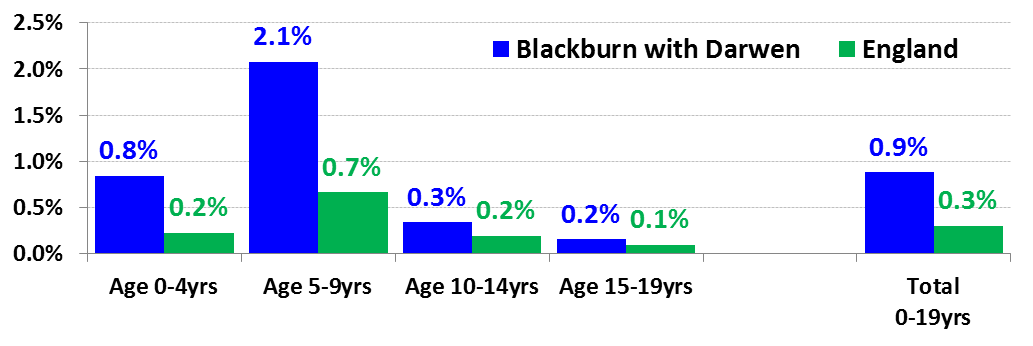

Primary Education - Key Stage 2

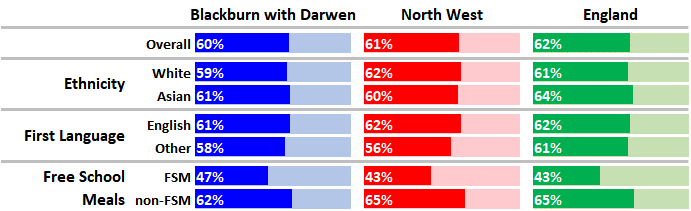

At the end of primary education, 60% of Blackburn with Darwen pupils in 2017 achieved the new more stringent ‘expected standard’ in reading, writing and mathematics (England 62%) (44). There is little difference, either locally or nationally, in the performance of White and Asian pupils, or those with or without English as their first language (Figure 35). Blackburn with Darwen children entitled to Free School Meals (FSM) still do less well than their non-FSM peers, although the gap is not as big as regionally or nationally. On the previous tests, the borough had the second best results outside London for FSM pupils, but that has now slipped to 12th best (or 41st place overall).

Figure 35: Key Stage 2: % achieving ‘expected standard’ in reading, writing and mathematics, 2017

(overall, and broken down by ethnicity, first language, and Free School Meal status)